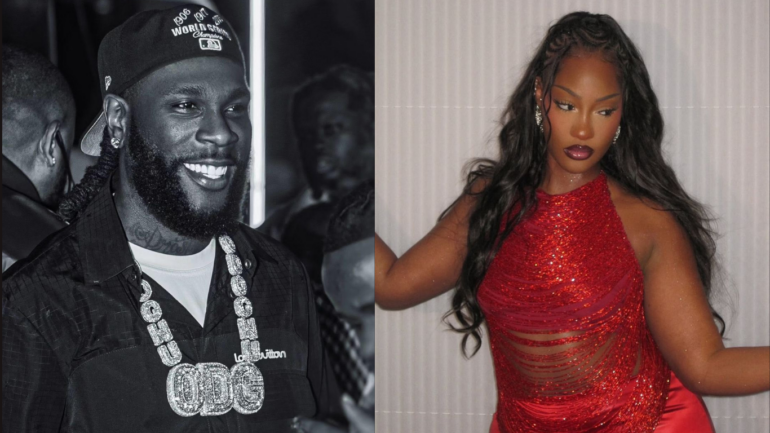

Nigerian rapper Jeriq has pushed back strongly against the long-standing narrative that Igbo artists fail to support one another in the music industry, describing the claim as misleading and disconnected from reality. Speaking on the issue, the Enugu-born rapper argued that collaboration, mentorship and encouragement among Igbo musicians are more common than critics admit, even if they are not always visible to the public.

The debate around Igbo artists and mutual support has circulated for years, especially on social media, where fans often compare regional solidarity in the Nigerian music industry. Some observers have suggested that artists from the South-East struggle to unite or promote one another as effectively as their counterparts from other regions. According to Jeriq, however, this perception overlooks the behind-the-scenes relationships and professional collaborations that exist within the Igbo music community.

Drawing from his personal experience, Jeriq noted that he has received significant support from established Igbo artists since the early days of his career. He pointed to collaborations and endorsements from figures like Phyno and Flavour as evidence that successful artists from the region do extend hands to emerging talents. For him, these gestures reflect a culture of encouragement rather than rivalry, even if every act of support does not play out publicly.

The rapper’s comments come at a time when Igbo-centric hip-hop and street music are enjoying renewed attention. Artists such as Jeriq, Aguero Banks and others have helped popularise a sound that blends indigenous language, gritty storytelling and modern trap influences. This movement has expanded the visibility of Igbo rap beyond the South-East, challenging older assumptions that music from the region lacks national appeal or internal backing.

Industry observers also note that collaboration among Igbo artists has taken different forms over the years. Rather than constant joint releases, support often appears through live performances, shared platforms, informal mentorship and strategic collaborations with artists who have already built national audiences. These quieter forms of support, Jeriq suggests, may be why the unity within the community is frequently underestimated.

While the conversation about regional solidarity in Nigerian music is unlikely to disappear, Jeriq’s stance adds an important perspective from within the scene itself. His response highlights a growing confidence among Igbo artists who believe their work, relationships and progress speak louder than popular stereotypes. As the South-East music movement continues to evolve, voices like Jeriq’s are reshaping how unity, success and support are defined in the Nigerian industry.